|

warrior bodhisattva

Super Moderator

Location: East-central Canada

|

Quote:

Originally Posted by pan6467

I would like to see 1 case where they proved a non smoker died from lung cancer due to working in a bar that allowed smoking. Or where a non smoker suffered serious health issues from working in a bar.

|

This might shed some light on this issue:

Quote:

Toronto smoking ban leads to decline in hospitalizations

André Picard Public Health Reporter

From Tuesday's Globe and Mail Published on Monday, Apr. 12, 2010 8:58PM EDT Last updated on Tuesday, Apr. 13, 2010 4:11AM EDT

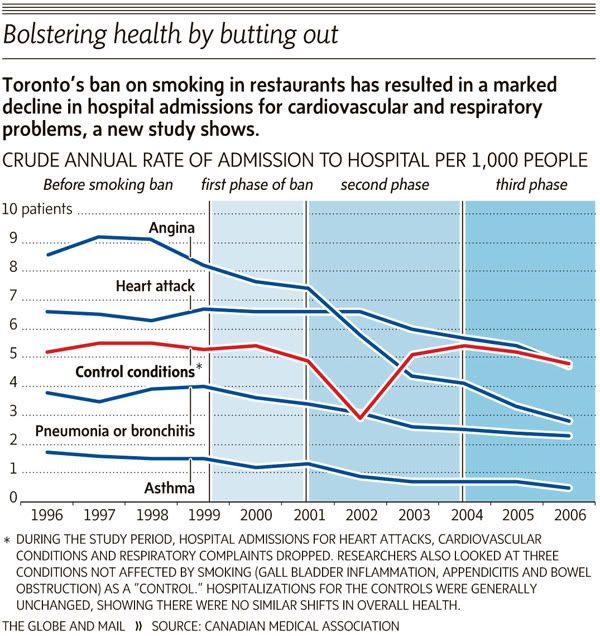

A ban on smoking in restaurants is being credited for a precipitous drop in hospital admissions for cardiovascular and respiratory problems.

The findings, published in Tuesday’s edition of the Canadian Medical Association Journal, are based on data from the City of Toronto.

The research shows that, in the three-year period after anti-smoking bylaws were implemented in restaurants, hospitalizations for heart conditions fell 39 per cent and for respiratory conditions 32 per cent. The number of heart attacks also declined 17 per cent.

“Healthy public policy has to be based on evidence and studies like this one validate the use of legislation,” said one of the study's authors, Dr. Alisa Naiman, a fellow at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.

She stressed, however, that new rules were not solely responsible for the dramatic health dividends that came about.

The study is based on an analysis of hospital admission data for the 10-year period between 1996 and 2006 that spans a period before and after a smoking ban was implemented in Toronto. Researchers also looked at data from two other jurisdictions where there were no smoking bylaws – Halton in suburban Toronto and Thunder Bay in Northern Ontario – for comparative purposes.

The City of Toronto introduced controls on public smoking in three distinct phases: In 1999, it required all workplaces to be smoke-free; in 2001, smoking was banned in all restaurants and; in 2004, the ban was extended to bars.

The research shows that during the first phase, hospitalization rates barely changed, likely because most workplaces were already smoke-free.

But when the ban on smoking in restaurants was introduced, the number of hospitalizations for cardiovascular and respiratory conditions dropped, almost overnight.

When smoking was banned in bars, the drop in hospitalizations was, again, modest.

“I think this reflects the fact that a lot more people go to restaurants than bars,” Dr. Naiman said.

While hospital admissions dropped sharply after no-smoking rules took effect in Toronto restaurants, the rate of admissions for heart attacks jumped by almost 15 per cent in Halton and Thunder Bay, while hospital admissions fell a more modest 3.4 per cent for cardiovascular conditions and 13.5 per cent for respiratory conditions.

Dr. Naiman said this shows the impact of legislation but also serves as a reminder that during the period studied, 1996 to 2006, there were other important policy changes. Those include increases in tobacco taxes, new advertising rules for tobacco products, graphic warnings added to cigarette packages and increased awareness about the dangers of smoking, and second-hand smoke in particular, not to mention non-legislative changes such as improvements in the treatment and management of chronic health conditions like asthma and angina.

“Legislation is just one part of the puzzle, but it’s an important part,” Dr. Naiman said.

Dr. Richard Stanwick, chief medical health officer for the Vancouver Island Health Authority, said the impact of smoking bans is seen not only in the statistics but on the ground.

Shortly after Victoria introduced a smoking ban in restaurants in 1999, he said, “there was a reduced need for cardiologists – we actually needed one less.”

Dr. Stanwick said there is a lot of other anecdotal evidence of the benefits of restricting smoking, but ultimately it is a quality-of-life issue. “Smoking and second-hand smoke cripples and disables people, often in their key productive years,” he said.

Dr. Stanwick believes legislation should be expanded and the next frontier is banning smoking in cars where children are present, and in parks and on playgrounds.

In a commentary also published in today’s edition of the Canadian Medical Association Journal, Dr. Alan Maryon-Davis of the department of primary care and public health sciences at King’s College in London, said the new research “adds to the growing body of evidence that legislation banning smoking can save lives, and that it begins to do so quickly.”

At the same time, he said, anti-smoking legislation raises the wider issue of how far government should go in using enforcement to improve public health.

“What is the optimal balance between laissez-faire-ism and nanny-state-ism when it comes to promoting health and preventing ill health?”

He said the role of health professionals should extend beyond treating the consequences of unhealthy behaviours such as smoking to advocate for prevention and legislation, but only where it is backed by sound evidence.

About six million Canadians are regular smokers, just over 21 per cent of the adult population.

|

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/...19/?cmpid=rss1

__________________

Knowing that death is certain and that the time of death is uncertain, what's the most important thing?

—Bhikkhuni Pema Chödrön

Humankind cannot bear very much reality.

—From "Burnt Norton," Four Quartets (1936), T. S. Eliot

|